True North

Thanks to a commission, I made my first trip to Svalbard three years ago. I barely knew its name and I certainly would have struggled to put the archipelago on the map, halfway between the North Cape and the North Pole.

It was discovered in July 1596 by the Dutch explorer William Barents who was looking for a northern route to China. He thought that these islands belonged to Greenland and named them Spitsbergen (pointed mountains). Since 1920, their name is Svalbard (Cold Coast), when the area came under the sovereignty of Norway.

Travelling to a different continent gives us a change of scenery, but going to Svalbard is a change of universe.

We lose our sense of time and place. It is bright for six months and the night is sixteen weeks long.

The light is probably what makes Svalbard. It can be extremely clear and crisp, but can quickly become, diffused, soft, imprecise and dark. It plays with the monochromatic landscapes and offers a limited spectrum of colour but so rich. From one photograph to another, the light changes and heightens the impression that everything is still to start.

It is like a call, I went back five times.

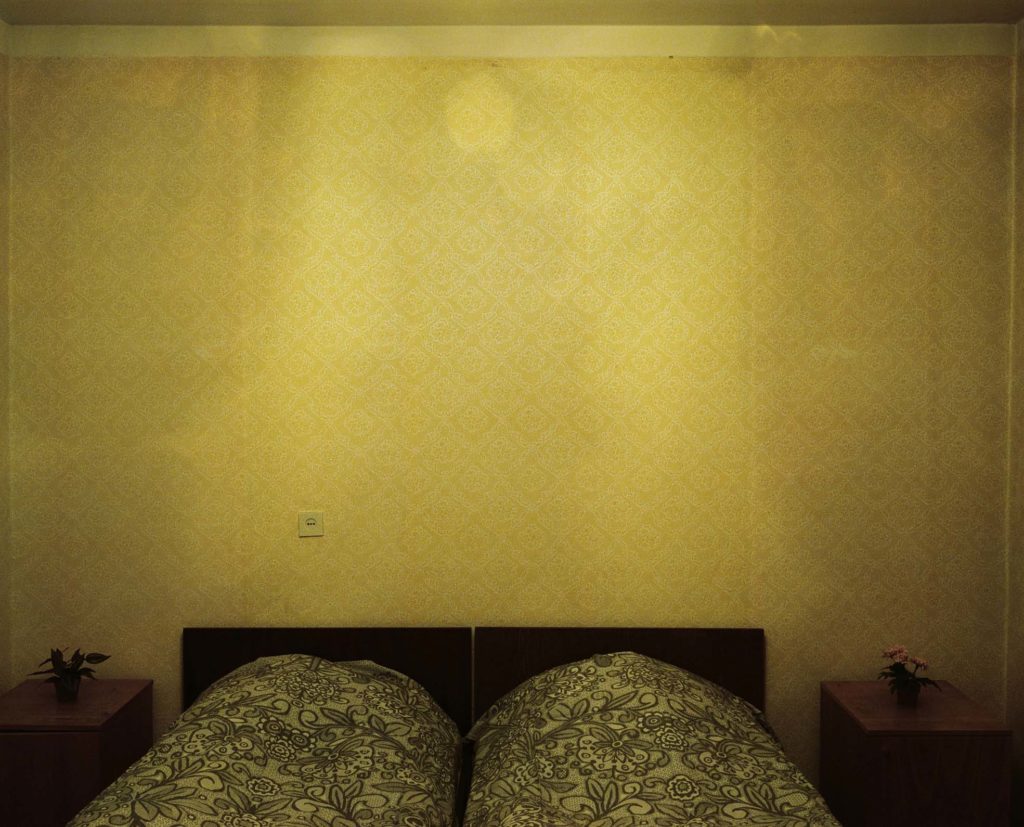

Barentsburg was my third destination, established in 1932; it is the last Russian settlement in the Arctic. I wanted to stay there so I booked a room in the only hotel for 15 days. It proves to be a small town, few streets and a mine, which is grim, run down and melancholic. The snow is covered with coal dust and you hardly see anyone outside. Six hundred people from Russia and the Ukraine work there on two-year contracts: 400 men and 200 women. Last summer, because of the limited amount of coal left, half of the population was asked to leave and the only school was closed. Barenstburg might live its last days.

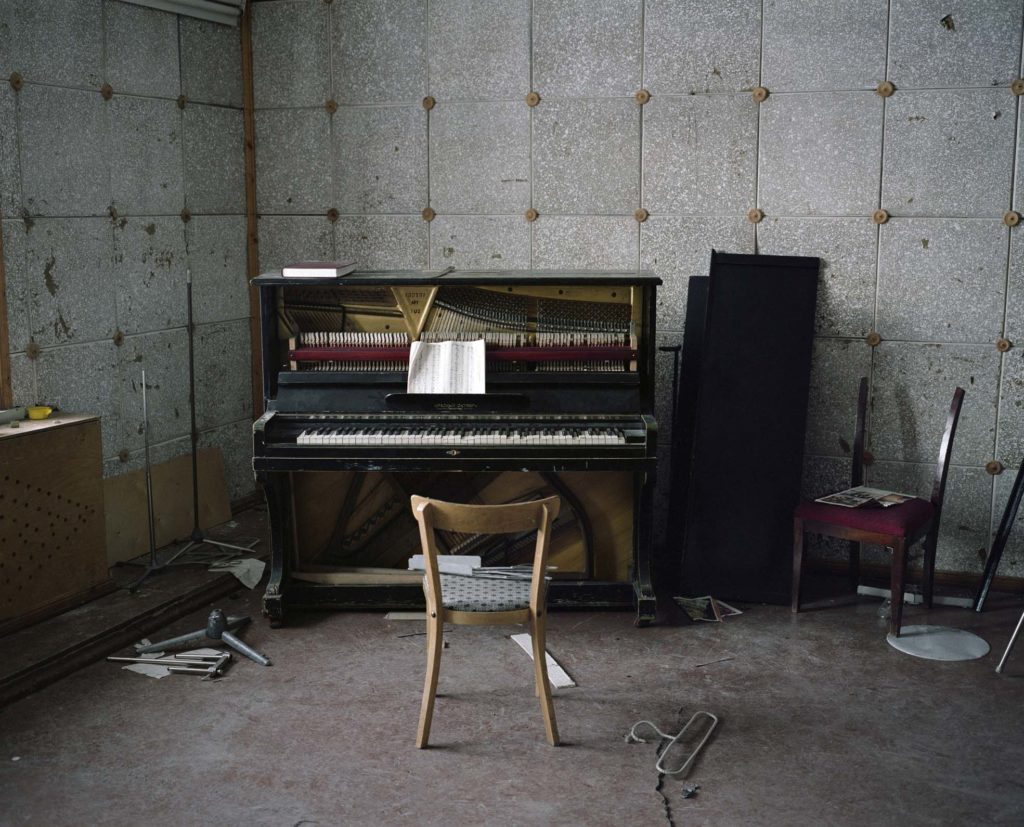

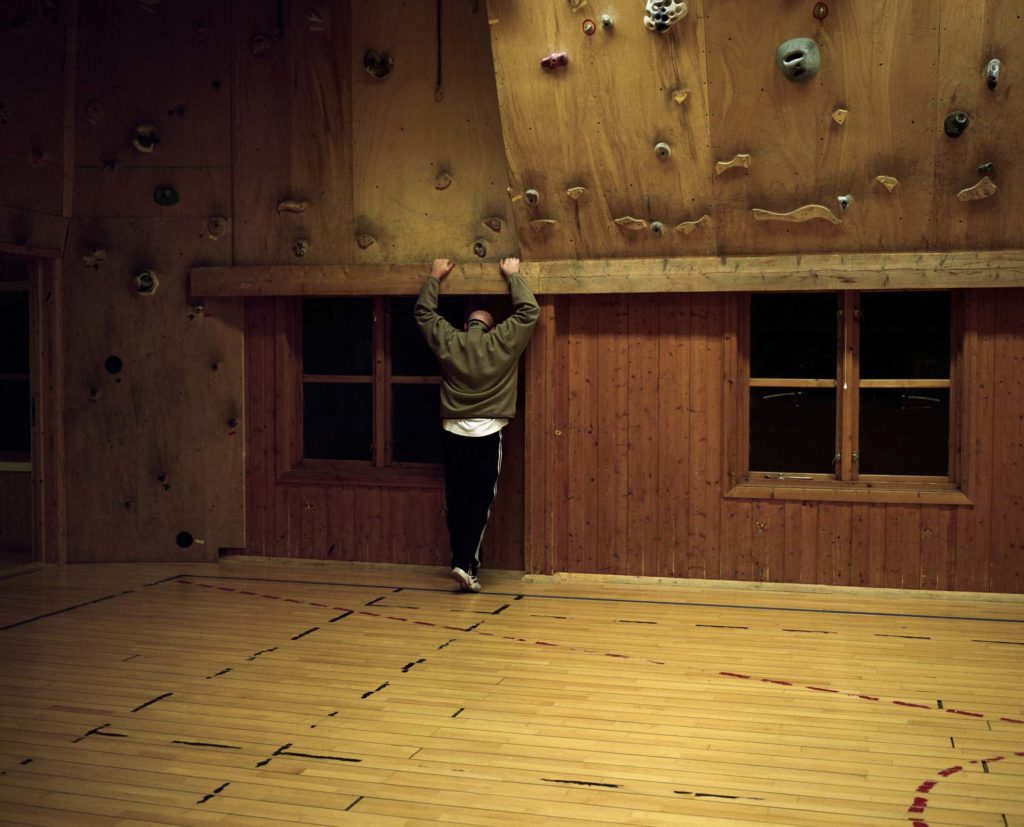

I went to Pyramiden for few days, a Russian mine closed since 1998. You don’t really notice it at first but there is no activity. Its buildings still stand, deserted, it feels like a film set. You come across the swimming pool, the sports club, the cinemas, and everything has been left behind. In the library all the books are on the shelves. In the indoor basketball court the balls have been left on the floor. We go to the cinema, to the projection room, and all the films are still stacked there. It feels as if you can hear the people who lived there – just like when you’re in a room where a party has just finished, and there’s a lingering sense of the voices and the music. Everything seems as if it is waiting to be used. It’s all on the verge of happening, you would just have to put the heater on and life would start again.

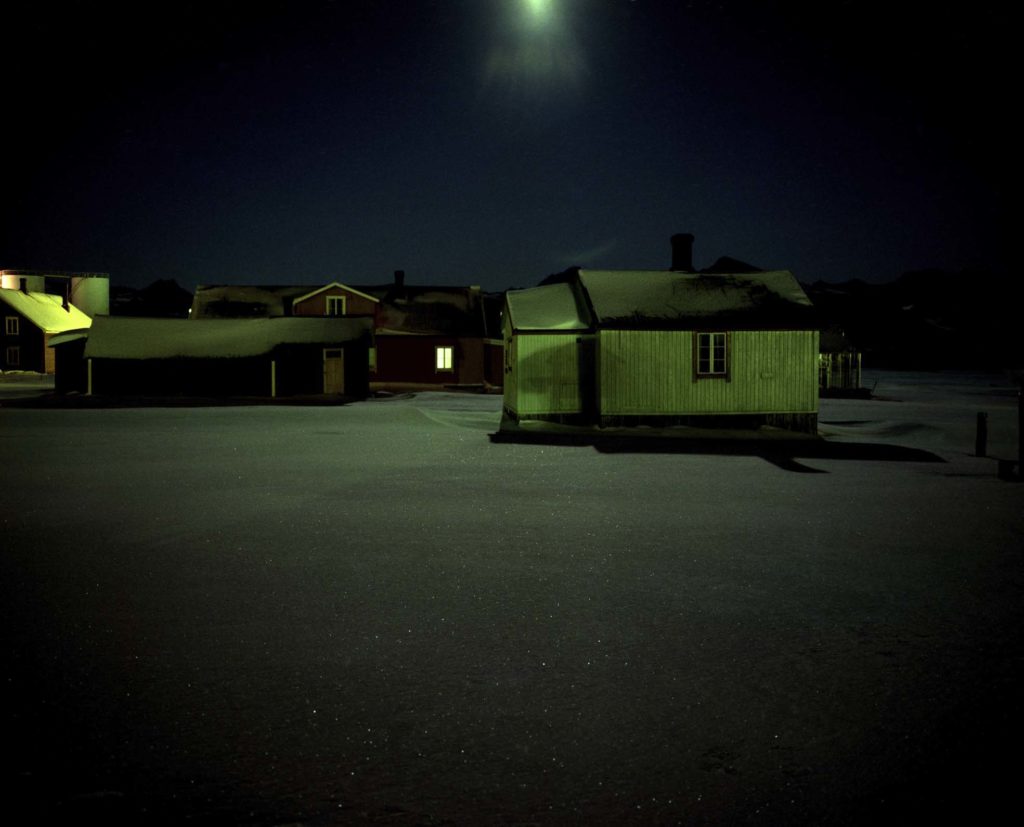

Ny-Alesund was my last destination, a disused coal-mining village. 30 scientists in the winter and up to a hundred in the summer work there. They are there to calculate, to measure the climate and atmospheric change, studying the wildlife, the flora and the marine life. The results are not always good.

Like Barenstburg, Svalbard might be living its last days. Its lands so hard and so fragile are victims of the global warming, they change inexorably. The American novelist Gretel Ehrlich calls them “the vanishing landscapes”.

True North

C’est grâce à une commande que j’ai effectué mon premier voyage dans le Svalbard, il y a trois ans. Je connaissais à peine son nom et j’aurais certainement eu du mal à placer cet archipel sur la carte, à mi-chemin entre le cap Nord et le pôle Nord.

Il a été découvert en juillet 1596 par l’explorateur hollandais William Barents qui recherchait une route du nord pour la Chine. Il pensait que ces îles appartenaient au Groenland et les baptisa Spitsbergen (les montagnes à la pointe aiguisée). Leur nom est Svalbard (la côte froide) depuis 1920, quand l’endroit est passé sous la souveraineté de la Norvège.

Voyager dans d’autres continents est évidemment dépaysant. Mais se retrouver à Svalbard, c’est changer d’univers. On y perd rapidement toute notion de lieu et de temps. Il fait continuellement jour pendant six mois de l’année et la nuit est totale pendant quatre mois.

La lumière est certainement ce qui fait l’identité de Svalbard. Elle peut briller et éclairer avec une extrême netteté, mais très vite, elle peut devenir diffuse, douce, indécise, sombre. Elle joue avec ces paysages monochromes, et offre une palette de couleurs restreinte, mais si riche.

D’une photographie à l’autre, la lumière change et accentue l’impression que tout est toujours à recommencer. C’est un appel aussi. Je suis retourné à cinq reprises au Svalbard.

J’ai rencontré différentes communautés, comme à Barenstburg, village minier Russe existant depuis 1932, le dernier en Arctique. A son apogée plus de 1500 habitants y vivaient. Depuis, une certaine mélancolie s’est emparée du village, et lors de mon passage, ils n’étaient plus que 600. Cet été, faute de charbon à extraire, le nombre d’habitants était encore divisé par deux. La seule école a été fermée. Barenstburg vit ses derniers jours.

Ny-Alesund fut ma nouvelle destination. Ancien village minier, trente scientifiques en hiver et jusqu’à cent en été y vivent désormais. Ils sont tous là pour calculer, mesurer les changements climatiques et atmosphériques, étudier la faune, la flore et la vie marine. Les résultats ne sont pas toujours bons…

A l’image de Barenstburg, Svalbard vit peut être ses derniers jours. Ces terres si dures et si fragiles à la fois, sont victimes du réchauffement climatique: elles changent inexorablement. L’essayiste américaine Gretel Ehrlich les appelle “The Vanishing Landscapes”, les paysages qui disparaissent.

DEG0386122.jpg

DEG0386123.jpg

DEG0386124.jpg

DEG0386125.jpg

05

DEG0386129.jpg

07

DEG0386132.jpg

DEG0386135.jpg

DEG0386138.jpg

DEG0386141.jpg

DEG0386144.jpg

DEG0386147.jpg

DEG0386151.jpg

DEG0386155.jpg

DEG0386156.jpg

DEG0386157.jpg

DEG0386158.jpg

DEG0386159.jpg

DEG0386160.jpg

DEG0386162.jpg

DEG0386163.jpg

DEG0386166.jpg

DEG0386167.jpg

DEG0386165.jpg

DEG0386168.jpg

27

DEG0386169.jpg

29

DEG0386170.jpg

31-Ny-Alesund

DEG0386171.jpg

DEG0386172.jpg

DEG0386173.jpg

DEG0386174.jpg

36

DEG0386175.jpg

DEG0386176.jpg

DEG0386177.jpg

DEG0386178.jpg

DEG0386179.jpg

Gautier Deblonde

Gautier Deblonde